Digitizing the Music Industry’s Data

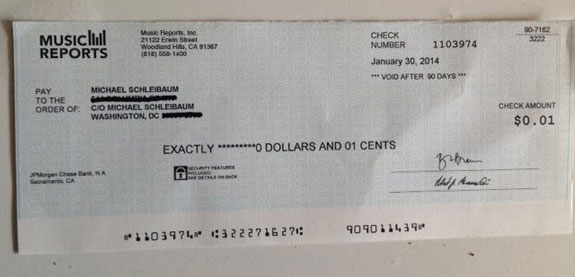

There’s never been more data available within the music industry for collecting, analyzing and reporting. Album sales and downloads, streaming data, YouTube views; all of these clicks feed into a breathtakingly massive mountain of 1s and 0s that mean dollars and cents to artists, labels, producers, managers and, to some smaller degree, outlets that sell or provide access to musical output.

The problem? There aren’t systems in place to transfer the data as easily as it is generated, nor is there a method for translating the information at the speed of light and make it understandable instantly.

Two new companies—Kobalt and DistroKid—were recently profiled in a brief article by Bobby Owsinski in Forbes, who points to these companies as frontrunners in what could be among the biggest demands and needs for music industry insiders, from label executives down to indie bands just trying to get their music released.

With 325 employees in 10 worldwide offices, Kobalt pledges a unified, dedicated staff “all focused on helping artists, songwriters, publishers and labels do what they do best,” according to Kobalt’s website.

The company was created in 2000 by Willard Ahdritz who saw the cracking and weakening of the music industry’s infrastructure “with a vision for the critical role that technology could play in creating a more efficient, fair and transparent music industry,” the website states. If listeners were getting better digital products, why shouldn’t the industry itself make changes to get better data?

The problem, as explained by Forbes reporter Owsinski, is that the current bookkeeping methods used by the industry are paper-based. Not that paper is problematic on its own, but all that data (sales, downloads, clicks, streams, sales, to say nothing of royalties, copyrights, credits, samples, etc.) has to be manually entered from one massive database to another. As Owsinski notes, this is often the work of an intern or some low-ranking employee, who might not have the appropriate skills to make the calculations required to ensure everyone is properly, and quickly, paid for their work. As a result, data can go missing, get messed up or be improperly filed.

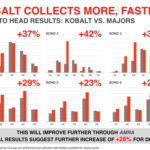

“We create technology solutions for a more transparent, efficient and empowering future for rights owners, where artists, songwriters, publishers and labels can trust they will be paid fairly and accurately, regardless of how complex the digital world becomes,” Kobalt’s website pledges. “Our innovative technology includes the world’s most advanced global licensing, collection and payment platform, our YouTub song matching tool Proklaim, one of the leading global digital music distribution platforms AWAL, and the award-winning real-time data and insight reporting Portal.”

The company boasts some 8,000 artists and songwriters among its clients, representing 600,000 songs and 500 publishing companies. Accolades from musicians ranging from Joel Martin (Eminem’s publisher) and Ryan Tedder of One Republic to Bon Iver and Miles Davis’ catalog—also? Paul McCartney and Moby and Placebo and Skrillex, to name a handful—line the margins of the company’s website. The only thing missing, at least on first glance, is an explanation of how this magic all works and how Kobalt is able to fulfill its stated promise of “Collecting 20-30% more money, faster,” but that’s understandable. It’s likely the company has developed some highly-guarded proprietary wizardry to ensure all the digital dollars and cents find their proper homes quickly.

Turning to DistroKid, the difference between the two services becomes apparent. Kobalt is for established artists, while DistroKid is for newcomers, smaller bands or artists just starting out. The testimonials on DistroKid’s home page include Derek Sivers, the found of CD Baby, calling the service “amazing” and promising he’ll “be sending everyone I know to DistroKid now.”

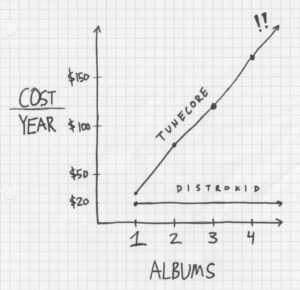

This service is one “for musicians that puts your music into online stores so that people can buy it,” the company says. That’s pretty simple. It appears DistroKid works with iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, Google Play, YouTube, Tidal and more than 150 other services, for a fee of $19.99 a year for unlimited uploads. DistroKid also promises a monthly payment of all royalties owed and release of material “10-20x faster than any other distributor, at a fraction of the price.”

What’s interesting about DistroKid is it allows artists to provide the service with a breakdown of how royalties are to be distributed. Have a five-member band where the song lyrics were written by two of the members, the individual artists were responsible for their own music, and as a result there’s an odd and very specific breakdown of how everyone should be paid? No problem. Give the service the breakdown and everyone gets every penny they’re owed, no muss, no fuss.

Unfortunately, that’s about all the information DistroKid has publicly available without signing up for the service. There’s no “About Us” page or list of client, but there is this fun little graph comparing the fees charged by DistroKid with those charged by its competitor TuneCore:

A search for any reference to blockchain, another concept of great interest to the music industry that promises an independent, centrally-located and easily searchable database that would keep meticulous records of song sales and royalty distribution, on both websites turned up nothing. Whether there’s anything to take from that absence is unclear. (Watch this space for details on three other companies working in the blockchain realm soon.)

But it’s clear that more music and more data means better recordkeeping systems are in high demand as the music industry evolves.

“How soon other aggregators, labels and publishers offer similar features to Kobalt and DistroKid remains up to conjecture, but these companies are certainly leading the way down a path that the rest of the industry will be soon forced to follow. It’s a process that everyone would like to employ tomorrow, but as with so much else in life, it’s also much easier said than done,” Owsinski correctly concludes.