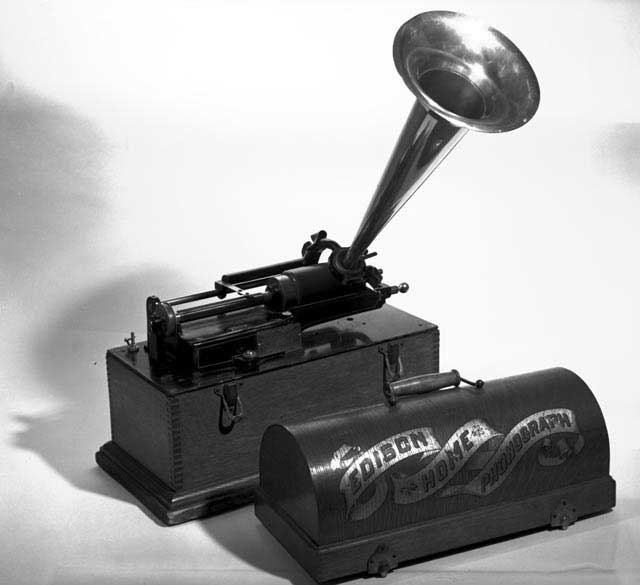

The ability to store sound for later playback has only been with us since the invention of Edison’s phonograph in 1877. But it wasn’t until we got deep into the 20th century that we got good at actually preserving these sounds for the long term. Those old recordings have degraded or are in formats that cannot be played back by any conventional means.

Physics Today (yes, I often read such things) has this look at new techniques pioneered by particle physicists to bring these old sounds–and this old music–back to life.

Historic sound recordings of the late-19th and early-20th centuries represent a small but diverse snapshot of the world, taken as a great transition was under way. The age of information technology was arriving, and at the same time, traditional experiences and ways of life were being displaced, transformed, or eliminated. In the research sphere, first-generation anthropologists, linguists, and ethnographers—among the earliest researchers to adopt sound recording as a tool for scientific fieldwork—captured bits of that global transition. Instrumental and vocal performances that earlier could only be experienced live—in a theater, a church, a parlor, or by a campfire—could now be experienced over and over; the result was a huge increase in the appreciation and creation of musical and related performing arts. The heroic inventors of recording technology left us their experimental recordings, their apparatus, and their notes, documenting their creative process and the emergence of a modern technology. Early recorded sound is consequently a world treasure.Nowadays most recorded sound is stored on digital media, but initially sound was stored analogously on a great variety of materials, including foil, lacquer, metal, paper, plastic, shellac, and wax, and in photosensitive emulsion. Recording formats included a variety of undulating grooves, latent images, and polarizations. Also wide ranging are the forms of degradation and damage, including abrasion, breakage, chemical decomposition, delamination, dirt, fading, mold, overplaying, oxidation, peeling, and warping.

The preservation and restoration of sound recordings must deal with all the factors described above and, not surprisingly, presents unique challenges. Several of us at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, working in close collaboration with the Library of Congress and others, have studied the problem and developed some solutions. The work described in this Quick Study has allowed researchers and the public to listen to a variety of “unplayable” key historical documents. Still, many media and modes exist that remain to be addressed, and our work is far from done.

Continue reading. It’s good.