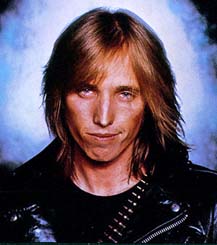

Though Quintessentially LA, Tom Petty Remained Rooted in the South

[An appreciation of Tom Petty by guest blogger John Duffy. -AC]

On the afternoon of February 10, 1964, a thousand bands were born in suburban garages across North America. Pubescent kids would meet grasping sweaty-necked guitars, electrified by what they had seen the night before.

The Beatles had made their first appearance on Ed Sullivan’s variety show. And the musical landscape of the English-speaking world would never be the same. They had three chords in their trick bag and fire in their hearts. Tom Petty was one of them.

But rock and roll would become more than a way to rebel, to meet girls, to bring adolescent fantasy into reality. For Petty, it was an identity, a safe place. For over forty years it was his family.

Petty’s untimely death from apparent cardiac arrest on Oct. 2 at age 66 robbed us of one of the most distinctive voices in all of rock. The hits are many, and we’ll not eat up space with a condescendingly short list.

The product of an alcoholic, abusive father and a doting mother, Tom grew up (by his own words) white trash in a college town. Gainesville, Florida is home to the University of Florida, but let us never forget the old truism: “in Florida, the more North you go, the more South you get.” In the chaos of home, music became young Tom’s “normal.”

Inevitably in any cultural explosion, most of those February ’64 bands wouldn’t last through spring. Those that soldiered on became the true breed. They were the desperate ones for whom no other occupation seemed suitable.

For Petty, that meant paying gigs at frat houses, steak joints, even strip clubs. It meant dropping out of high school and eventually scraping together enough money to drive to Los Angeles in a one-shot stab at fame.

Born in 1950, he was generationally speaking a Boomer, but when his first band of fellow Florida expats—Mudcrutch—stalled in the early 70s, he was forced to elbow his way in as an orthodox rocker for the Blank Generation. He captured them completely, then doubled down and took hold of their younger Gen-X siblings, the ones who weren’t into the gangsta rap or the brooding melancholy of Nirvana (and frankly many that were).

He did it by harnessing the energy and gestures of punk and mixing in the melody and mechanics of the British invasion, along with the sunny jangle of California folk-rock.

And all of it was painted over with a rounded Southern snarl that could be equally confrontational, seductive, and generous. With success came permanent residence in—and identification with—Southern California, where he lived the last forty-five years of his life. But the South remained in him, in his voice, in his worth ethic, and in his artistic hospitality.

And though his escape from a chaotic childhood meant an escape from the South itself, the mark the place made on him remained perhaps the most important element in his art.

It’s the one thing I carefully listened for on every new album, in every performance, and I was never disappointed. Only rarely did he try to explore the persistence of this unshakeable identity. After all, the South meant home, and that meant memories of abuse.

In 1985, the album Southern Accents was meant to be an exploration of that cultural burden of Southern identity. The centerpiece was a tune called “Rebels,” in which a down and out man seeks to blame those “blue bellied devils” for his current troubles and shouts “Down in Dixie!” with the same ironic pride as the out of work veteran in Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” only a year before.

Petty has called the album a failure. Its tinny 80s production hasn’t weathered well. But at its heart is perhaps one of his most underappreciated songs over the last forty years: the title track.

Over a slow gospel piano, slide guitar, and gentle strings, the singer—with equal amounts of pride and regret—declares that everything; working, talking, praying is done with a Southern accent “where I come from…”

The region is deep in the singer’s bones, tattooed on his soul for better or worse. He sleeps off a bender in an Atlanta jail and thinks of heading to Orlando to pick oranges if there isn’t an early freeze (yes, it freezes in Florida). In the song’s final verse, he dreams of his mother kneeling over him and saying a prayer. Petty’s own mother had died only five years before.

It’s not a stretch to see the symbolism. The mother; nurturing, loving, comforting, warm is what people like Petty hope the South could be. The drunk, marginally employed was his father; the South’s troubled past.

The tour in support of Southern Accents even used the Confederate flag as iconography: it covered the entire stage backdrop. And even though he could easily have taken a stance of “it was different back then,” he apologized for doing so in 2015 after nine black worshipers were killed in a Charleston, South Carolina church by a white supremacist.

“I wish I had given it more thought. It was a downright stupid thing to do,” he wrote in Rolling Stone. When people started bringing Confederate paraphernalia to shows in the 80’s, he asked them to stop. And they did.

Tour versions of “Southern Accents” in recent years (it was rarely played after its initial release) gained resonance, truth, and dimension with Petty’s advancing age.

On Highway Companion (2006), “Down South” explored the personal economics of returning to a place of mixed emotions. Petty sang about his intent to “sell the family headstones…make good on my back loans.” Even after an entire career away from the angels and ghosts of his youth, he still sought closure.

All of this honesty earned him the reputation of a rock and roll authentic, someone so personally and musically reliable that earned him the unequivocal admiration of his musical peers.

It’s no wonder that the Heartbreakers were the first self-contained band Bob Dylan worked with since the Hawks, or that Johnny Cash enlisted them to play on his mid-90s American Recordings career reboot.

He was in a band with one of those very Beatles who first ignited his musical passion. He was the first person Dave Grohl said yes to playing drums for after Kurt Cobain’s suicide. And when people accused Petty of mimicking the Byrds on “American Girl,” Roger McGuinn responded by recording the tune on one of his own albums. The two remained close friends. And if there exists a spiritual bridge between the Southern rock of Skynyrd and the Allmans and the modern storytelling of the Drive-By Truckers, it is undoubtedly Petty.

Biographer Warren Zanes said shortly after Petty’s death, “Rock and roll came knocking on HIS door.” Zanes meant that literally, but it is true in a spiritual sense as well. Forever connected to his cultural roots—even as he sought distance most of his career from the very place—Petty’s voice was forever genuine.