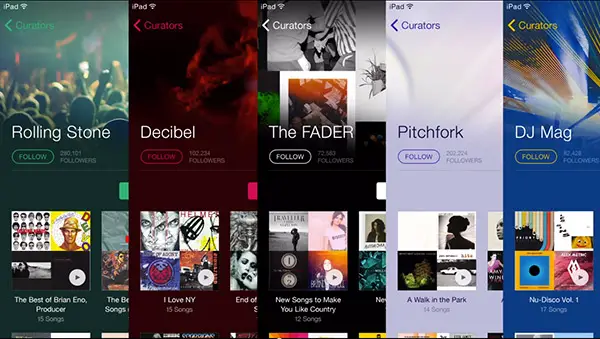

Playlists: Individually Curated or Label-Created?

What role should record labels play in the creation of curated playlists on streaming music services, and how much influence should the preference of individual listeners have on songs presented to them?

During a recent session of Midem, an international music industry conference in France, panelists discussed the phenomenon of streaming services relying on playlists being curated in-house by actual people, instead of letting algorithms make all the choices. As Musically.com noted, Spotify’s playlists are raking up a billion streams per week, to say nothing of playlists randomly thrown together based on a user’s feedback.

About 20% of playlists were being curated by “other,” which includes lists created by Spotify itself, or those owned by a particular record label or other sources, according to Slice Music’s Justin Barker. Another 40-50% of playlists came from Spotify’s “collections—the playlists that users create themselves and what they add to their libraries. Deezer, on the other hand, counted playlists as 40% of its streaming traffic, “half of it coming from user-generated playlists and the rest of it from professional-generated playlists,” noted the company’s Alexis De Gemini.

Some of these lists are coming directly from the record labels – the lists contain artists housed on a single label and its imprints, meaning users who choose those playlists are only exposed to one “family” of artists or, possibly, one genre of music. Sammy Andrews, of Entertainment Intelligence, said this kind of practice hurts indie artists and smaller labels that don’t have the money for that kind of dedicated exposure. It’s something indies should be doing, and likely would if the funding weren’t prohibitive, but there’s an advantage of being late to a trend—they can avoid the mistakes the major labels previously made.

“When we come out of the doors with an independent playlist brand, it will be an incredible playlist brand,” she promised. But “getting the entire world’s independent community together has been a challenge…and there are a lot of conversations to be had about who pays.”

Slice’s Barker said some playlists are “pitchable,” while others, especially those owned by labels, are pretty well locked in and cannot be altered or modified by artists who might not be on the label that curated the list.

This alone should and could raise the ugly specter of “payola,” the illegal practice of labels paying radio stations to play certain songs more than others. Originally a scandal in the 1950s and 1960s, although Billboard Magazine claims it was an issue for vaudeville in the 1920s as well, payola was in the headlines again in 2002 as Sony BMG executives admitted they made deals with several large commercial radio station chains in the US and agreed to pay $10 million in penalties. There’s a difference between pay-to-play and payola, by the way: According to the US Federal Communications Commission, pay-to-play is the practice of bands paying for the ability play onstage, whether in a battle of the bands-type competition or, as was attempted, on larger stages including the NFL’s Super Bowl halftime show. As for the exchange of money for playing a certain song on commercial stations, it’s legal so long as the station discloses it was paid to play that song. This disclosure can be done in any of several ways, including an on-air announcement or legal language included somewhere on the station’s website. It’s still a practice largely criticized by artist organizations and those that support musicians, including the Washington, DC-based Future of Music Coalition.

But back to the subject at hand.

Spotify, it turns out, has its own system for pitching and selecting playlists. It involves a form that must be filled out but is made available to all labels, but it contains a quota of space up for consideration during a given week. Labels or artists who want to have their tracks considered must make an argument for why their particular song or songs should be included, but that doesn’t mean any feedback will be provided, whether a song is selected or ignored.

“A lot of those playlists are very political…you need to justify why Track X is at number five and Track Y is at number 10,” Barker added. “And a lot of the time that’s fueled by data from whatever source. And also, Spotify will look at what’s performing on the platform” and guide its decisions based on whatever’s popular at the moment. Again, it’s not exactly opening the doors for new artists to find their way into the playlists or the ears of new fans. So much for streaming as the great level playing field for introducing new artists.

Andrews asserted that “the mix of human and algorithmic curation is important; human curation struggles to fully scale as the volume of music (and the number of users with individual tastes) continues to grow,” Musically’s Stuart Dredge writes.

Traditional radio, Barker noted, might decide to play a song over and over until listeners start calling in and requesting it. Not everyone falls in love with a song on the first listen; not everyone will love it after 50 either. That’s true for streaming services curating playlists—if building a playlists based on feedback from listeners voting with thumbs up or down, know that it might take a while for a song to catch on.

Another sidebar—traditional radio DJs typically base their playlists on listener requests, reports on which songs in which genres are getting the most hits on services like Shazam, local sales data and other information. There’s also the art of scheduling songs so they don’t play at exactly the same time every day. Streaming services, in a modern twist on the aforementioned payola, might receive extra funding from labels to include songs on playlists based on artists that wouldn’t necessarily match the featured artist; say, including Coldplay on playlists or Pandora stations for Michael Bublé. (Thanks to my go-to DJ friend for that insight.)

De Gemini from Deezer said “collective intelligence” is vital to mix the data collected from listener preferences and the selections of curators and pull a playlist together.

“What I don’t believe in is to take only hard science into account,” added Vincent Favrat of Musimap. “The curators at Deezer want the machines to help them to be ultra-humans: to be closer to their emotions…they want to be empowered to make 100 times more playlists than they are used to doing, to get the music to the right people.”

De Gemini later said that while people might claim to want to be the first to find new music, that’s not likely the truth. Instead, listeners “want to listen to the songs they love over and over again. It’s part of our problem.” However, if a recommendation for a song is tagged as a “personalized recommendation,” it could be introduced amongst songs a person already likes, increasing the odds of it being included on other lists in the future. Deezer is working on developing a method that would allow users to express whether they’re in the mood to discover new songs or listen to favorites.